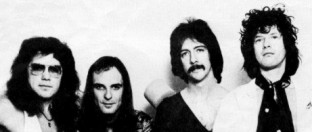

KIM MITCHELL of Max Webster

By Greg Quill

There's something about Kim Mitchell that makes you fear the worst. His obsessive outspokenness is as much a trademark as his manic guitar breaks, or his fine-boned lunatic grimace. People tell stories about him, about his single-minded quest for recognition and stardom, about his withering fury and blistering sarcasm, about his secret pacts with dark envoys. People know Kim Mitchell as a force. And they know, sooner or later, he'll have things his way.Imagine the relief when I recently confronted a quiet, concillatory Mitchell, polite, even modest. And this in the aftermath of a failed British tour by Max Webster this winter in which advance ticket sales had been so poor, all the band's prestigious headlining appearances had had to be hastily cancelled.

"Kim struck by mysterious throat infection", read press releases that slinked back from what was to have been a conquered, at least battered, nation of Max converts. Press releases -- Kim loathes them as much as he despises the hypocrisy of the industry he battles daily and that now seeks to claim him.

"It had been two years since the previous English dates", he said, "and I knew we'd lost that initial support. Ten dates were offered this time, then four, but I was still insisting on a heavy support tour instead. Eventually I agreed to go over and just make some noise -- four dates, that's all.

"Things weren't together again. The promoters had almost taken a pass because the press didn't really know why we'd come so 'unannounced'. It was a very bad tour. We ended up playing two supports with Black Sabbath".

Twenty-three thousand dollars and ten days later, Max returned home, philosophically reconciled to the fact that Europe, potentially their most important market, deserved better planning, a more concerted effort next time.

"My hopes are that after the next album, we'll forget about Canada and the States for a while and go for Europe right away," Mitchell continued. "I mean, just reverse our usual game plan.

"I have a big boner for the kids over there. They're totally uninhibited -- real punters."

The last time Kim spoke with Canadian Musician he was bitter and grim. Max's previous U. S. record label had withdrawn much needed tour support finances for a follow-up to their rousing introduction to British audiences some months before, and though A Million Vacations had acheived platinum status in Canada, the band would soon disintegrate. Embroiled in a power and direction struggle with keyboardist Terry Watkinson, whose commercially acceptable material qualified Vacations' success even though it clashed dramatically with Mitchell's tense, hazardous style, Max's creative personnel would eventually be reduced to the band's originators -- Kim Mitchell and lyricist Pye Dubois.

Fighting from an unfriendly corner, Mitchell retaliated with Universal Juveniles, a monster guitar album, cracking with pugnacious scorn. He wrenched improbable shapes from his own fear and frustration with such self-righteous rage that he simply demanded attention. And got it. Universal Juveniles instantly established Max Webster in the United States after years of futile effort. Already the British press hail it as a heavy metal classic. Internationally, it's the biggest record the band has ever had, and it's pulling their past work along with it.

Now, with his instincts strengthened, with a new American label (Mercury) obviously convinced of his crazy genius, with his differences with Watkinson resolved, and with another quitar player in the band (Steve McMurray) who stimulates him, Kim Mitchell's past bitterness is lately assuaged.

"We've decided the next album will be more democratic", he said. "Tunes will be welcomed from everyone in the band given a fair hearing. I haven't been enjoying the role that seems to have been thrust on me, to tell you the truth. You know, my picture on the cover, Kim Mitchell as Max Webster -- I feel uncomfortable with that. I want to feel part of a band again. This business is so crazy that one person can't do it by himself."

Even so, while recounting his artistic disputes with his previous U.S. label, Mitchell's purposeful aggressiveness somehow diminished his vision of a republican Max.

"You can't compromise if you're a genuine artist. Eventually it comes down to the fact that you've got to do what you've got to do. When you're delivering something you really love, that's been a part of you, it comes out so much stronger than anything that may involve compromises based on commercial potential or money considerations," he said.

"So anything written by members of this band will get recorded as long as we're all into it. If it's not comfortable, we won't do it. Even if it's one of my tunes."

Universal Juvenile's undisputed high point is the technically unwieldy, musically nuclear amalgamation of Max and, label partners, Rush on "Battlescar", a track so huge and monolithic it almost defied the capacity of conventional recording techniques to capture it. Though the combination of Canada's two heaviest bands in a single, virtually live session was accomplished at the insistence of Rush's Geddy Lee, probably Mitchell's most forceful apologist, Kim said there's an unpleasant feeling from certain quarters that Max is getting ahead on someone else's popularity.

"I guess it's a reality to outsiders, but I see it as a bunch of guys working on an artistic level, all getting off on one thing. It was a great day. Pye told me there were fans outside the studio cutting off their ears and slipping them under the doors," he laughed.

Produced by Toronto's Jack Richardson (veteran of Guess Who's hit years, Alice Cooper, Poco and Bob Seger sessions, among hundreds of others), and recorded at Phase One Studios in Toronto, Universal Juveniles' only shortcoming, as far as Mitchell is concerned, is what he calls a certain "west coast smoothness" in the overall sound.

"It works fine. It's very even from bottom to top, and everyone likes it, but to me, after all the times I've listened to it, it's not hard enough," he said. "When I put my earphones on and crank it up, I like to feel my head pop on snare and bass drum beats -- that doesn't happen with this album."

In pursuit of head-popping hardness, he thinks the next Max effort will be recorded in Quebec's Le Studio, in Morin Heights, where Rush's latest, Moving Pictures was done. They'll probably also use Rush producer Terry Brown, he added.

Though he's riding a wave that seems to have swept him clear of imminent destruction with only seconds to spare, Kim's tenuous check on his own fears and artistic ethics kept our conversation returning to aspects of professional ruin that obviously preoccupy him. Even in prosperous times, he worries -- if not about himself, about musicians he's close to. One recently departed Max member was pressed out of service by domestic concerns, he remembered, by an inability to reach a compromise between the rock 'n' roll dream and the values of the real world.

"Pye and myself are idealists, so I guess it's easy for us. But when Dave left because his wife needed him at home, I thought, well, if he feels he has to, it's best to split.

"I just had to say something though. I said, 'Look, I respect you for making a decision on your life, I just think it's a waste of a good musician. And you're going home to sell plastic forks for the Kentucky Fried Chicken business -- I think you could have held that off for a while. That would have always been there.'

"I've seen that happen too many times."

In positive times, though, Mitchell is encouraged by the number of great new Canadian bands he feels are beginning to take some risks.

"I think Streetheart have a great album (Drugstore Dancer), I think Loverboy have a great album. And guitar players -- there are so many good solos on new records; the guy in UFO -- I hear things on the radio lately that just make me want to practice. By the time we start the next album, probably in July, I want to have some real hot new licks to play.

"My favourite guitar player these days is Alan Holsworth. I saw him this last time in England in a little bar, and he blew me away. I like unique players. As much as I can't stand Zappa's lyrics or affectations, as a guitar player, he's great."

Kim said he's not all that comfortable working on other people's sessions, though he knows it's something he should work at -- for the challenge and the discipline. Ian Thomas, another Anthem stablemate, is releasing a new album featuring some of Mitchell's work; he said recently that Mitchell was the perfect studio guitarist for his requirements.

"Yeah, well, to be honest with you, I felt like I was in a Steely Dan session", Kim smiled. "The guy came down on me so hard -- everything had to be in it's place. I'm one of those guys who plays a solo straight up -- the way it happens, more or less. Then Ian would pull the solo apart in minute sections, tell me which parts to keep, what to repeat, and I'd have to teach myself what I'd just played, note by note."

What he does get to hear on radio these days is less than deliberate -- moments snatched away from his home. Kim said he gave away his tuner and record collection -- a radical protest against Toronto radio programming policies of which he has long been a vociferous critic.

"I have about three albums in my collection right now", he said. "Captain Beefheart's Doc At The Radar Station is one. I love that guy. People say he's too weird. I say, sit down and try to play one of his tunes. He's coming from a different world. He's wonderful. I also have the new Rush album. I picked it up at the office for free, and Tom Robinson's Sector 27 which was also given to me. I did buy the new Weather Report album and the new Pat Metheny, and that's about it as far as my collection goes.

"FM radio is compromise city now. I can't listen to it. And I'd rather not have to go through the things other people think are necessary to get airplay. I'd much rather do what I do and if it gets played, that's great. And lately it has been getting played, and thanks a lot -- I think you people are wonderful," he said with a sweeping gesture meant to embrace punters and Max Webster programmers alike. "But I can't deal with the 'sell, sell, sell' of it. It's like a nagging wife somewhere in the background. Before I sold my tuner, I only listened to classical, or jazz, or ethnic music stations -- things that weren't so hyped up all the time. Now there are stations playing Max and I love it. But if they stop, I'm not going to get out the razor blades.

"From now on I'll play what I want to play", he repeated "and if they don't like it... well, I know I shouldn't say that, but every now and then I have to. Otherwise, I'd be psychotic."

He pondered again the fate of people forced to exist outside the boundaries of their natural instincts and talents, in what he calls the "Big V-8 Cow World". It matters very much to him that he be allowed to continue doing things his way.

"I feel very fortunate to be a guitar player," he said. "You don't have to inhale asbestos, sell your time, sniff fingers. I don't think I'd have the guts to go through the hell those people do..."

And still he remembers, with pleasure and irony, the months following his move from Sarnia, Ontario, when the prospect of playing the Running Pump in Toronto's outer limits, or the Gasworks on Yonge Street was the height of artistic fulfillment. Or when tough times drove him to second-string in showbands and country groups for months on end. Or when he met Terry Watkinson for the first time, penniless and sleeping on the floor of an abandoned suburban house. Or the year of blissful study with guitar master Tony Braden before his retirement.

"Initially, I moved to Toronto to study with Braden," Kim said. "Max Webster was supposed to be a side thing to pay for lessons and practice what he taught me. Life was wonderful then. Every week you knew you were getting ahead. I loved taking lessons. I lived for it. A lot of my style comes from that one year."

Now he suspects that whatever happens, those days are behind him. Even if Max is, in the final analysis, too bizarre for the 'Real Big Time', Mitchell knows he's safe. He knows he's made a mark, that his guitar style -- a great straining arc circumscribing almost surreal tension -- is now the subject of scrutiny, of respectful attention.

He enjoys detailing aspects of his playing, his equipment, his pursuit of style. Somehow it befits his status now; the artist's reward is the oppotunity to discuss his craft.

He told me he uses two completely different set-ups, one for studio work, the other on stage.

"They're completely incompatible", he said. "I've never been able to adapt one to the other. On stage, what works for me is two stock Fender Deluxe Reverbs, 22 watts each; a basic MXR distortion unit; an MXR flanger; a Roland Stereo Chorus unit; a Strat with PAF super distortion pickups; and a great booster built by the guys at The Music Shoppe in Thornhill (outside Toronto). I call it the LSD booster because I've never been able to figure out what makes it work so well.

"I want to mention those people," he added. "They've always been great to me -- Lloyd, Warren, Peter. They get all my work."

Kim said he recently bought a stock Gibson Les Paul, the first he's ever owned, to obviate the characteristic electronic buzz Strats are occasionaly prone to -- usually when he's standing in front of 15,000 people.

"I had Bill Lawrence pickups put into the Les Paul," he added, "because the custom pickups are so microphonic. I found I could only get around half the normal Strat level before the Les Paul started taking off on its own. The Lawrence pickups also have a pole tap. You can shut one pole off so you don't lose the bright sound at low volume."

He also owns two acoustic guitars -- mostly for practice -- a Martin D-35 and an ancient Fender flat top. "I find that if I can run off a scale at a reasonable rate on one of them, I can peel out three times faster on the electrics."

In the studio Kim plays through a 100 wat Hi-Watt head and Marshall cabinets with Celestion speakers.

"Celestions have a real tight distortion," he said. "I find JBL's are a little ragged in the top end for me, and other speakers tend to peak into the sibiliance range and blend with the cymbals or something.

"I have a nightmare every time I go into the studio. I guess every guitar player does. It seems so easy on stage -- you just plug in and get your sound. But in the studio I do that and find it sounds completely different when I get into the control room.

"I love talking about this stuff. Do you want to know what kind of strings I use?" he laughed.

He seemed surprised when I said yes, and laughed again. "Regular slinkies. They work OK".